November 2024

NASA's Mission to Jupiter's Moon Europa

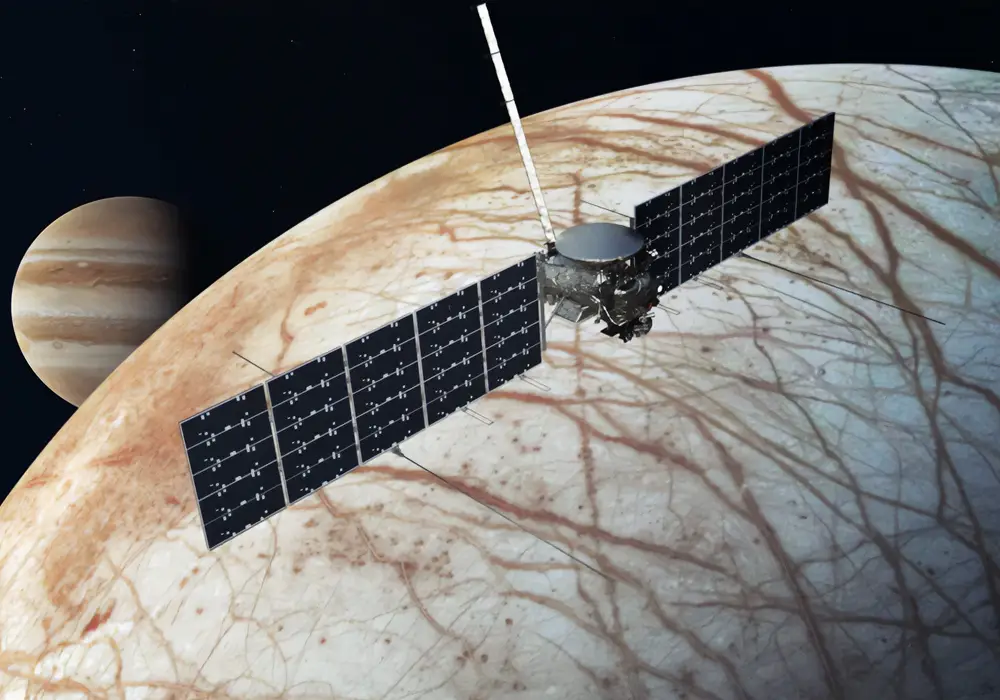

On Monday, October 14, 2024 NASA launched the Europa Clipper mission on a six-year journey to Europa, a moon of Jupiter that may be hospitable to life as we know it. Europa is one of the four moons of Jupiter discovered by Galileo in 1610. Galileo’s discovery of satellites orbiting Jupiter showed that not everything in the heavens revolved around the Earth, one of the discoveries that put Galileo at odds with the Roman Catholic church that still believed in the Earth-centric model of the Universe. Today, Europa takes on new significance since it is widely considered to be the most likely place in our solar system beyond Earth to have existing life. Below its frozen surface, Europa has a global ocean of liquid water. Since we find life existing everywhere on Earth where there is water, the Europa Clipper mission’s goal is to understand if Europa is a place where life might exist today. Europa Clipper is the first mission dedicated to exploring Europa, and it is the largest interplanetary spacecraft ever launched by NASA. Since Jupiter is 5.2 times farther from the Sun than Earth, sunlight is more than 25 times fainter and the Europa Clipper needs a very large solar array to provide 700 watts of power when at Jupiter. As shown below, the solar array is composed of two “wings”, each 46.5 feet (14.2 m) wide and 13.5 feet (4.1 m) high. The full spacecraft is 100 feet (30.5 meters) long and 58 feet (17.6 meters) wide, about the size of a basketball court. The artist’s concept below shows Europa Clipper above an actual image of Europa taken by NASA’s Galileo mission. [The Galileo mission launched in October 1989 and arrived at Jupiter in December, 1995. During 1995–2003, the Galileo mission observed Jupiter and the four Galilean moons plus a fifth Jupiter moon, Amalthea.] The entire Europa Clipper spacecraft weighed 13,000 pounds (~6,000 kg) at launch with nearly half of the weight, 6,000 pounds (2,750 kg), being fuel (propellant) to steer the spacecraft during its mission. Propulsion is provided by monomethylhydrazine / mixed oxides of nitrogen. Over 50% of the fuel will be used to slow Europa Clipper down and insert it into orbit when it reaches Jupiter.

Artist’s concept of Europa Clipper over Europa, with Jupiter in the distance. The white boom extending upwards in the graphic is the magnetometer instrument boom.

Credit: NASA

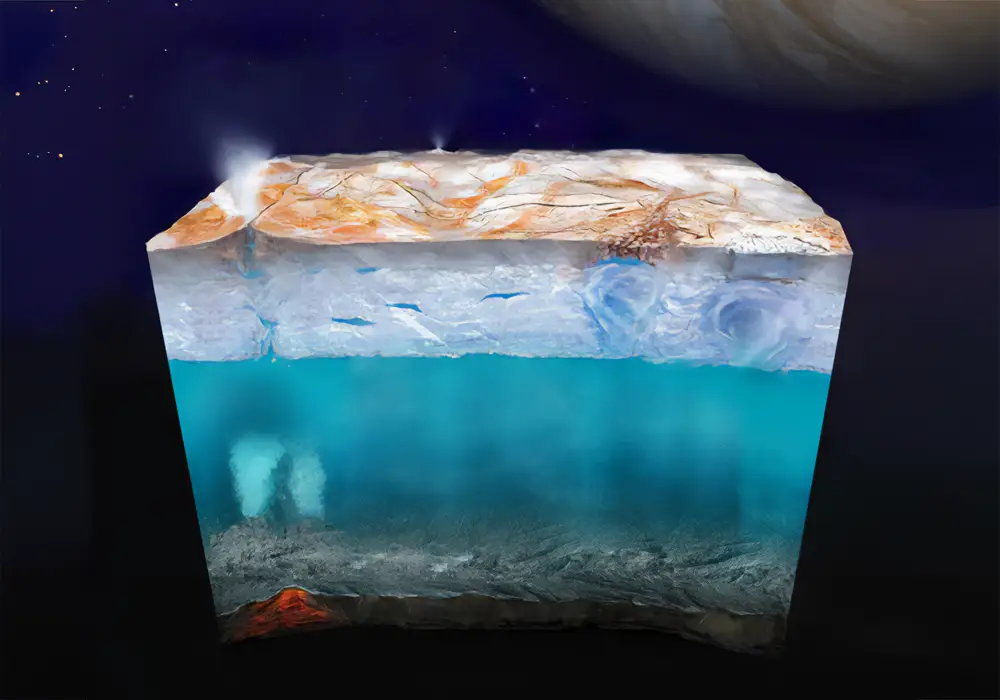

Europa has an equatorial diameter of 1,940 miles (3,122 km), about 90% of the size of the Earth’s moon. But Europa is 5.5 times more reflective than the Earth’s moon. [The Earth’s moon is actually quite dark, with average of 14% albedo (reflectivity); the Earth’s moon is similar to the color of asphalt.] Europa is thought to have an iron core, a rocky mantle, and a saltwater ocean that is 40 to 100 miles (64 to 161 km) deep covered by a layer of ice that is 10 to 15 miles (16 to 24 km) thick. The brown lines seen in the Europa image above are places where the ice is thought to have cracked, allowing some of the liquid ocean to come to the surface.

Artist’s concept of Europa’s ocean and ice layer.

Scientists think that under the icy surface of Jupiter's moon Europa a saltwater ocean exists that may contain more than twice as much liquid water as all of Earth's oceans combined. This artist's concept (not to scale) depicts what Europa's internal structure could look like: an outer shell of ice, perhaps with plumes of material venting from beneath the surface; a deep, global layer of liquid water; and a rocky interior, potentially with hydrothermal vents on the seafloor.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Europa Clipper will not arrive to Europa until 2030 since the spacecraft needs to circle through the inner solar system to use the gravity of Mars and the Earth to slingshot the spacecraft to Jupiter. Europa Clipper is now headed to Mars where it will receive a gravity assist in late February 2025. Then it will circle back to a close approach with the Earth, getting a gravity assist in December 2026, after which Europa Clipper will have enough velocity to reach Jupiter in April 2030.

Jupiter poses a special challenge to science missions since Jupiter’s magnetic field is 20,000 times stronger than the Earth’s. This strong magnetic field creates a very large magnetosphere that traps charged particles streaming out from the Sun and from the volcanos of Jupiter’s moon Io. These charged particles can disrupt and damage spacecraft electronics and will induce charge tracks across the sensitive focal plane arrays used in imagers and spectrometers. Hence the Europa Clipper spacecraft and instruments are specially designed to shield as much of the radiation as possible.

Europa Clipper carries nine science instruments and a gravity experiment that uses the telecommunication system. The instruments, wavelengths sensed, and the type of focal plane array (FPA) are listed below.

- Europa Imaging System (EIS) - Two cameras, one wide angle (48⁰×24⁰ field of view) and one high-resolution narrow angle (2.3⁰×1.2⁰ field of view). The narrow field of view camera will achieve spatial resolution down to 50 cm. Each camera has a 2048×4096 pixel CMOS FPA that senses light from 350 to 1050 nm (0.35-1.05 µm). Over the course of the mission, the EIS wide angle camera will map 90% of Europa at a resolution of 330 feet (100 m).

- Europa Thermal Emission Imaging System (E-THEMIS) - Infrared imager for 7-14, 14-28, and 28-80 µm bands. E-THEMIS uses a 140×920 pixel microbolometer FPA. One of the science objectives of the E-THEMIS instrument will be to scan Europa’s surface to find relatively warm ice, which may be a sign of recent resurfacing. Other instruments will then target those areas to learn about the moon’s subsurface chemistry.

- Europa Ultraviolet Spectrograph (Europa-UVS) - 4096×4096 pixel multi-channel plate (MCP) with cross-delay-line (XDL) readout. The ultraviolet spectrograph will help determine the composition of Europa’s atmospheric gases and surface materials.

- Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa (MISE) - 421 spectral channels over 0.8-5.0 microns. Teledyne CHROMA-A 320×480 pixel HgCdTe FPA. MISE will map the distribution of ices, salts, organics, and the warmest hotspots on Europa. These maps will help scientists determine if Europa’s ocean is suitable for life. More information on MISE is presented below.

- Europa Clipper Magnetometer (ECM) - The magnetometer boom is approximately 28 feet (8.5 meters) long, with three fluxgate sensors. Europa Clipper’s magnetometer instrument will measure the strength and orientation of magnetic fields during dozens of Europa flybys.

- Plasma Instrument for Magnetic Sounding (PMS) - The magnetometer (previously listed instrument) measures Europa’s magnetic field with the goal of determining the ocean’s depth and conductivity, and ice shell thickness. However the magnetic field will be distorted by the plasma (charged particles) circulating Jupiter. The plasma instrument (PMS) will measure the density, temperature, and flow of plasma near Europa, to help correct the measured magnetic field signal.

- Gravity/Radio Science - Europa’s gravity will affect the motion of the Europa Clipper spacecraft, which will modify the frequencies of radio signals received at Earth from the Europa Clipper spacecraft. Analyzing these frequency variations provides a measure of Europa’s internal structure and how Europa gets slightly distorted as it orbits Jupiter.

- Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-Surface (REASON) - Ice-penetrating radar will measure Europa’s icy shell and ocean, revealing the ice layer’s thickness. The radar will also study Europa’s surface elevation, composition, and roughness, and search Europa’s atmosphere for plumes of the ocean coming through the ice.

- MAss Spectrometer for Planetary Exploration/Europa (MASPEX) - The mass spectrometer will analyze gases in Europa’s atmosphere and measure the composition of any detected plumes. If a plume is detected and measured, it can reveal the chemistry of the subsurface ocean and how the high radiation environment of Europa alters compounds on the surface.

- SUrface Dust Analyzer (SUDA) - Tiny meteorites eject bits of Europa’s surface into space and the subsurface ocean may vent material into space. The dust analyzer will identify that material’s chemistry and area of origin, and may be able to measure the ocean’s salinity.

All of the science instruments will operate simultaneously on every flyby of Europa, enabling scientists to overlay the data to get a full picture of Europa. The location of the instruments on the Europa Clipper spacecraft are shown in the following animation.

Animation of the Europa Clipper spacecraft showing the location of the science instruments.

Credit: NASA

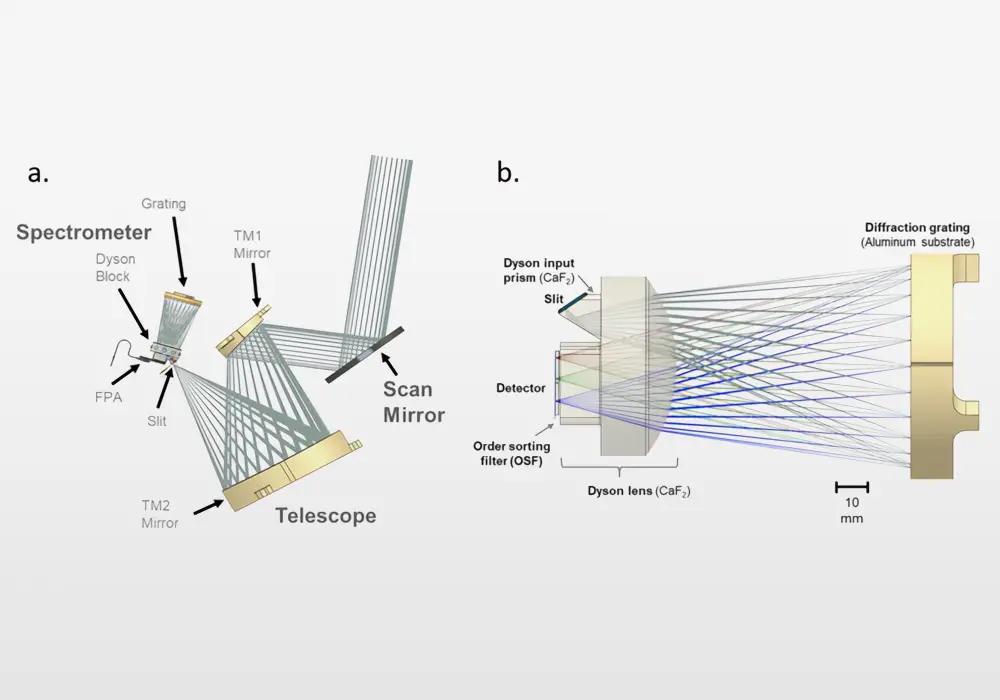

Spectrometry is one of the key tools that scientists use to determine the composition of materials on Europa, since the intensity of reflected and emitted light as a function of color depends on the type of material and its temperature. Each material has a spectral “fingerprint”. The measured spectrum of a single spatial pixel can be decomposed to see the fingerprints of multiple types of materials within the pixel.

The Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa (MISE) is an infrared spectrometer made by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) that uses an infrared FPA made by Teledyne. MISE will map the distribution of ices, salts, organics, and the warmest hotspots on Europa. The maps produced by MISE will help scientists understand Europa’s geologic history and determine if Europa’s ocean is suitable for life.

The MISE Optical Design. Figure a. (at left) shows the MISE optical ray trace. Figure b. (right) is an enlargement of the MISE Dyson spectrometer ray trace in detail.

Credit: Diana Blaney et al, “The Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa (MISE)”, Space Science Reviews (2024) 220:80.

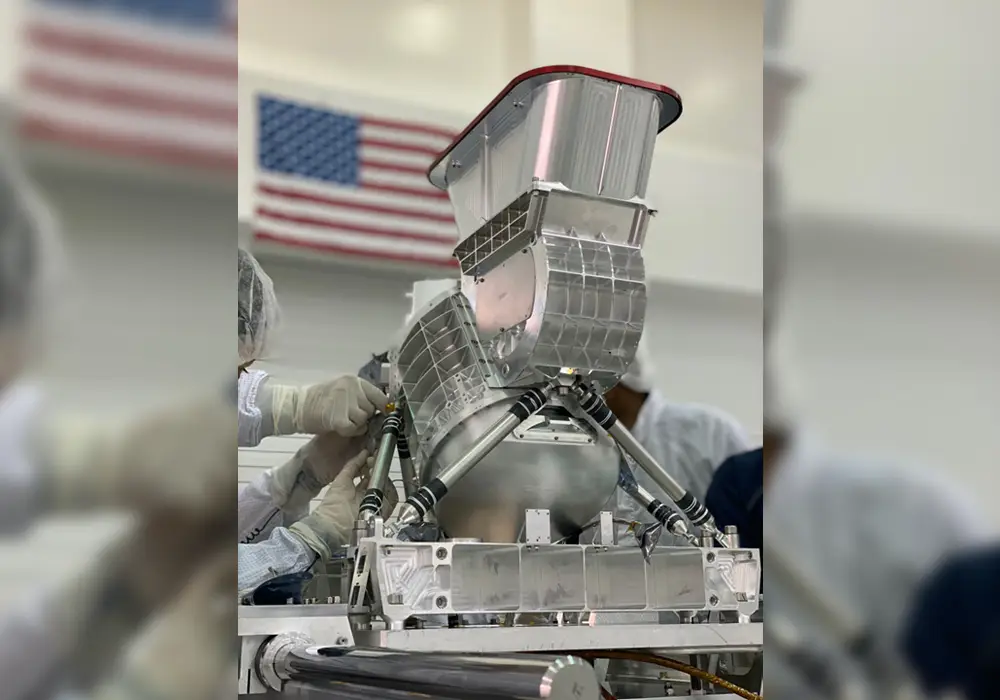

Europa MISE instrument after assembly in the clean room at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Credit: NASA/JPL/Caltech

MISE has a compact Dyson spectrometer that will sense light with wavelengths from 0.8 to 5.0 microns, dividing the light into 421 bins of 0.01 micron (10 nm). [Recall that the human eye can sense light with wavelengths from 0.4 to 0.7 microns. The wavelengths sensed by MISE are in the infrared, beyond what the human eye can see.] MISE senses the spectra of one row of 300 cross-track pixels each frame and builds up a two-dimensional spectral data cube as it flies over Europa.

The 0.8 to 2.5 micron wavelengths are essential for quantifying hydrates (compounds that contain water) and water ice, while the 3 to 5 micron wavelengths are required for detecting low abundances of organics, most radiolytic products (radiolysis is the dissociation of molecules by ionizing radiation), and discriminating salts from acid hydrates. The 3 to 5 micron wavelengths can also be used to measure thermal emissions from geologically active regions, if present.

Teledyne provided the infrared focal plane array (FPA) that serves as the “eyes” of the MISE instrument. The FPA version in MISE is Teledyne’s CHROMA-A , an FPA that is controlled by digital input signals and outputs an analog signal (thus the “-A” notation). To minimize the FPA area and optimize shielding, the CHROMA-A was customized with the minimum number of pixels. The CHROMA-A FPA is 320 columns (for the 300 cross-track pixels) and 480 rows, over which the 421 color bands are spread. The pixel pitch of CHROMA-A is 30 microns, a dimension that is tightly coupled to the MISE imaging spectrometer design. The FPA will always be read out at 18.2 frames per second, a cadence set by the high radiation environment that causes streaks of charge in the FPA when charged particles penetrate through the shielding. Longer exposure times will have too many streaks for image processing software to remove. The MISE CHROMA-A FPA was also customized for the amount of charge that it can detect, a quantity called “full well depth”, and has more analog outputs to ease the digitization rate of the focal plane electronics. Teledyne also optimized the CHROMA-A design to achieve a very low power version of the CHROMA-A ROIC (readout integrated circuit). The very low power enables MISE to cool the FPA to cryogenic temperatures (83-87K) without expending excessive power for FPA cooling. MISE has a 60W power budget that includes operation of all electronics and cooling of the spectrometer optics to 84-92K.

Teledyne also developed a prototype of the focal plane electronics (FPE) that operates the CHROMA-A FPA. Teledyne delivered the FPE schematic design and prototype unit to JPL, after which JPL fabricated and qualified the space flight FPE.

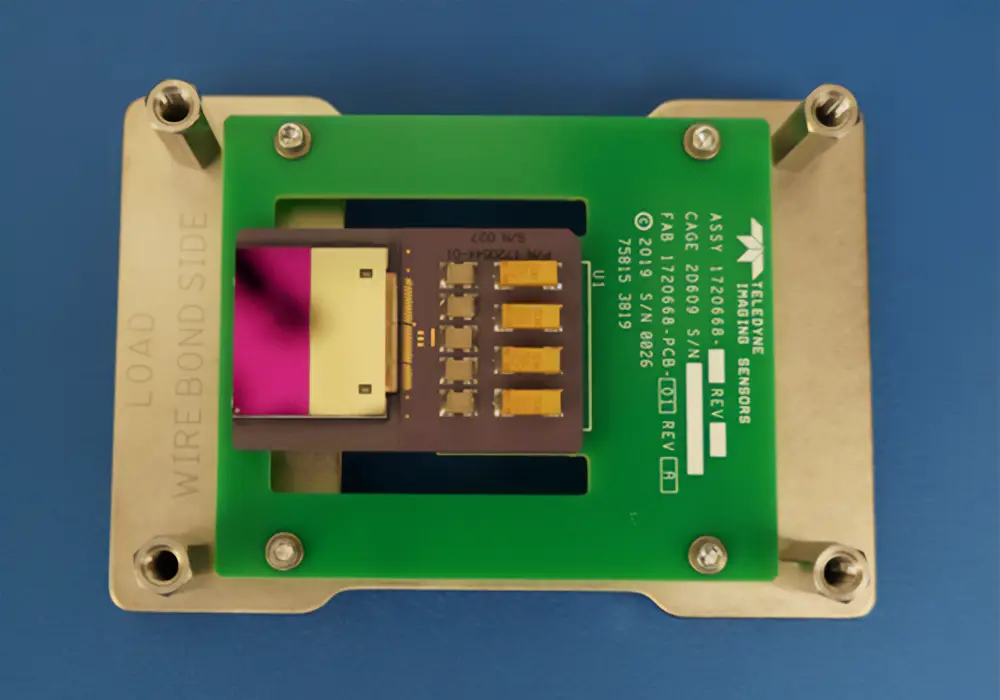

Photo of the Europa MISE instrument focal plane array (FPA). The FPA is a customized CHROMA-A that is 320 columns wide by 480 rows in the vertical direction. The FPA is the black square in the middle of the upper part of the package. The spectra of the 300 cross-track pixels are spread by the instrument optics along the columns of the array. The two white stripes to the left and right of the FPA are for mounting the order sorting filter (OSF) of the image spectrometer.

Credit: Teledyne & NASA/JPL/Caltech

Photo of the FPA with OSF mounted (rotated 90 degrees relative to the other FPA image). The OSF blocks unwanted colors due to the higher diffraction orders reflected by the diffraction grating in MISE. The 0.8-2.5 micron light is sensed under the gold blocking filter (under which are two zones of filter) and 2.5-5.0 micron light is sensed under the pink portion of the filter.

Credit: Teledyne & NASA/JPL/Caltech

Teledyne and JPL have enjoyed a long and very successful partnership. Teledyne has delivered FPAs to JPL for their Earth and planetary science imaging spectrometers since the 1990’s. Teledyne and JPL are now demonstrating a fully digital FPA for future spectrometers, an FPA named “CHROMA-D” where the “-D” denotes digital input and digital output. A 3072×512 pixel CHROMA-D FPA is planned for NASA’s Surface Biology and Geology Earth Science mission.